Learning impedance controllers from demonstrations

Robots need to regulate contact force in order to gracefully interact with the physical world. Impedance control is an implicit approach to achieve this. In impedance control, the robot does not directly measure and control the contact force but focuses on modulating its own dynamic behavior under the external wrench. For instance, a robot can act like a low-stiffness spring, which makes the regulation point, e.g., robot end-effector, yield to the external wrench so as to avoid a large contact force.

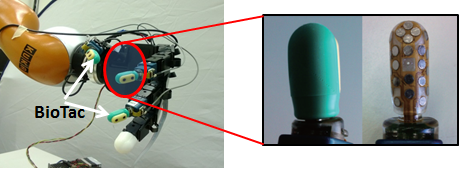

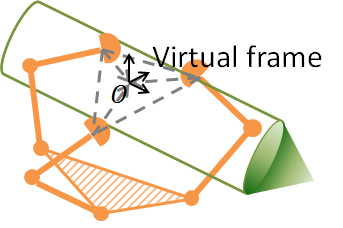

This research is about how can we let robots learn such kind of impedance controllers from demonstrations. This of course requires some assumptions about the robot dynamic behavior. One way is to assume that the robot adopts a constant impedance (taking stiffness as an example) parameter within a specific time window and tends to track a desired position and force profile. With additional constraints, one can formulate an optimization problem to extract a stiffness trajectory characterizing how the robot should react in face of motion deviation. We realize such an approach on a multi-fingered hand to realize compliant rotational motion. Now the dynamic behavior to describ is not the end-effector of a single manipulator but the manipulated object. The idea is to model and control the object behavior through a virtual-frame representation, which uses finger joint configurations and tactile sensing to surrogate the real object pose.

With recorded tactile information and object (a bulb) motion as demonstrations, the robot learns to insert the bulb into a socket with a variable impedance profile, e.g., increasing the motion stiffness at the end stage to overcome more frictions.

When force demonstrations are not available, we can still use kinematic data with additional assumptions. The idea is to take external force as disturbances and variability of demonstrations indicates the desirability to reject them. This boils down to learning quadratic cost functions whose reference point and weight matrices are to be identified. Specifically, when demonstration trajectories are closely distributed, one should expect large weight matrices to penalize deviations and vice versa. Then an optimal control approach can be adopted to get a feedback controller with varying feedback/impedance from the identified cost functions. Both learning and trajectory control can be handled in a probabilistic inference framework when the system dynamics or cost constraints are not easy to handle. Again, by utilizing the above multi-fingered controller, one can learn and implement the compliant motion for a handwriting task:

The motion compliance shows its benefit in handling some environment uncertainties, such as the writing surface with a variational orientation.

Find more in:

Papers:

Learning Object-level Impedance Control for Robust Grasping and Dexterous Manipulation

Learning Cost Function and Trajectory for Robotic Writing Motion

Repositories: